|

By Hannah Combs

On the wall of the Bonner County Fairgrounds office, a blue ribbon is framed and hangs prominently on the wall. In lustrous gold figures on the worn blue background are the numbers 1927, which is known as the year of the first Bonner County Fair. In 1927, before the fair moved to the area now known as Lakeview Park and decades before it moved to its current location on North Boyer, the fair was held at the Methodist Community Hall and livestock entries were penned in an empty lot across the street. It was a “tremendous success,” according to the Pend Oreille Review, with so many entries that there was hardly enough room for visitors to navigate around them. At the time, the focus was on agriculture and communities competed for awards as well as individuals. With award premiums totaling nearly $250, communities got competitive. The Sagle community was noted for creatively spelling ‘Sagle’ out of apples in their display. Colburn produced many novelty items, from Filbert nuts and popcorn to buckeyes and rabbit mincemeat. The Midas (Garfield Bay today) display, though the smallest, took home the prize for best spuds. But no one could beat the Sunnyside-Culver-Oden display, which was the largest and took home first place that year. Much of its success may have been due to Mrs. Ole Peterson of Oden Bay, who individually had more fair entries than most of the communities. She won awards for her elephant pears, turnips, cantaloupes, and just about every canned good imaginable. The story of the first Bonner County Fair is well known… or so we thought. At the request of Darcey Smith, current Fairgrounds Director, the Bonner County Historical Society’s research team dug into the early history of the fair, and what they found surprised us all. In the summer of 1908, an enterprising young politician gave a speech to the Sandpoint Commercial Club. Paul Clagstone had brought his new wife to the Hoodoo area a few years earlier and built a successful cattle ranch. As his prominence in the area grew, he took a shot at running for a seat in the state legislature. But in order to secure the vote, he knew he would have to win over the bigwigs in Sandpoint. He appealed to the Commercial Club that he could bring together all of the farmers for a county fair, saying “the displays could then be taken for exhibition at the Spokane Interstate fair and Bonner County and its resources would thus be doubly advertised.” With the Commercial Club’s support (and funding), the first fair was held that fall in the upstairs rooms of what is now Larson’s on First Ave, and its exhibits were later transported, fully intact, to Spokane. The 250 entries featured primarily fruits and vegetables since the building owners did not want livestock inside, but nevertheless the exhibits showed “a marvelous representation of Bonner County.” Over the next few years, the fair bounced between other improvised locations while the community tried to make plans for a permanent fair site. The Bonner County History Museum’s collection includes a few artifacts from these years, including an award slip from 1909 entitling Ethel Ashley to a $1.00 prize for her watercolor painting. The museum collection also boasts a silver-plated trophy from 1912 with the inscription ‘Best Apples.’ The fair ended after 1912 for unclear reasons, possibly connected to WWI, and the fair lay fallow for the next decade and a half. When it was revived in 1927, it appears the community was so excited that they forgot all about the earlier events. As we enter the 13th decade of Bonner County Fairs, agriculture is still one focus of fair exhibits, but many people now know the fair for its exciting livestock shows and auctions. Just like the origins of the fair itself were a surprise, when animals were first accepted in 1927, the entries were equally surprising. That year, Mrs. E.D. Blood of Dover took home the silver cup for her display of chinchilla pelts. Research courtesy of the Bonner County History Museum and Maggie Mjelde.  By Hannah Combs and Chris Corpus Young Vernon Shook didn’t let anything stand in the way of his ambitions to become an engineer or doctor, not even the Great Depression. Upon graduating from Sandpoint High School, he took on dozens of jobs to raise college funds. One was a short stint as a lifeguard at the Natatorium (indoor pool) in Wenatchee, WA. The next summer, in 1932, he came back to his childhood swimming hole and had a vision that would change Sandpoint forever. Up to that point in time, locals waded in the shallows around City Beach after the spring floods, cleared out driftwood, and danced around submerged logs that had escaped during log drives. Drownings occurred at the south end of the sandy area where the river started because of the swift current. The most notable was the young daughter of a local chief. Some say that was the beginning of the end of the annual summer Salish gatherings. Vernon’s vision for City Beach included a safe swimming area, lifeguard training, swimming lessons for children, and a picnic area for all residents to enjoy. Of course, his exuberance also included a twelve-foot high tower so the lifeguards could see all the swimmers, and, of course take a periodic high dive into the deep waters. The city leaders were hoping to entice tourism based on car travel, so they jumped at Vernon’s proposal. It helped that he was willing to do all of the work and be paid a pittance; but Vernon had a passion for his town’s cool waters. He cobbled together monetary donations and marshaled volunteer labor to create the first city bathing beach. After motorists learned of the new amenities, Sandpoint became known as having the best bathing beach in the Inland Northwest, complete with a fine bath house. It evolved from a seasonal gathering place for the Kalispel, to a part of the Northern Pacific Railroad land grant, and it was eventually conveyed to the city of Sandpoint for the express use of a public park. Periodic improvements took place over the next few years, but in 1939, a major renovation took place, thanks to financial assistance and labor through the Works Progress Administration. The entire beach area was dredged to fend off the impact of flooding. Submerged logs were removed, sand was bulldozed onto the beach to raise the land height, and houseboats were removed and demolished under guard of the sheriff. In addition to the bath house, a formal garden and arboretumwere designed, as well as a broad promenade. The 1948 flood decimated the park and its improvements, and prompted the building of Cabinet Gorge and Albeni Dams. The Sand Creek outflow was rerouted for the safety of beachgoers, and more dredging for an improved boat marina provided some of the fill needed to raise the land area even higher. After Shook’s impassioned efforts to create the first public area, credit the people of Sandpoint for providing much of the volunteer labor to make it what it is today. The Lions Club headed the main modern improvements, most notably the BBQ pavilion, and their Fourth of July events centered around the beach. And, thank goodness, the lifeguards continue their fine work. As for Vernon, he went on to a long career in social work, and was assigned by the United Nations as chief of the Displaced Persons Program in Rome following WWII. Even off the beach, he was still helping struggling people find their way safely home. Construction work unearthed rooms beneath the Abbott Block- but what is their history? By Lyndsie Kiebert

Courtesy of the the Sandpoint Reader When Heather Upton, Interim Director of the Bonner County History Museum, received a tip that secret rooms had been uncovered beneath the Abbott Building on First Avenue in Sandpoint, she responded as most history lovers would: with excitement and curiosity. "I immediately thought, 'Oh, secret rooms- there were amazing, nefarious things going on down there,'" Upton said with a laugh. As it turns out, Upton was likely on to something. The Abbott Building- located at the corner of First Avenue and Bridge Street- suffered from a large fire in February 2019. The structure has since been torn down, and amid cleanup and renovations, a series of underground rooms came to light. According to research from local historian Dan Evans, newspapers of the time painted a clear picture that the rooms beneath the Abbott Building and neighboring Walker Building- which were connected by an underground hallway- comprised an illicit gambling hub in early Sandpoint. One story, from December 1915, detailed a gambling raid in which sheriff's deputies guarded escape routes and cut phone lines while breaking up a gambling ring beneath the Walker Store. One gambler is reported to have escaped out the back of the building by sliding down a drain pipe and "vaulting across" Sand Creek, "evidently too frightened to think of warning the First Street resorts, thinking only of making good on his own escape." In 1924, an article titled "Officers Raid Gambling Den," recounted how law enforcement found "gambling going on full blast, about $80 being on the table in the game." Local historian Nancy Foster Renk is also well versed in the many iterations of the Abbott Block. Aside from the known gambling that took place in the basement, Renk said the space once served as a meeting place for the Sandpoint chapter of the Industrial Workers of the World or "Wobblies"- the organized labor group responsible for the local 1917 lumber strikes. The governor of Idaho at the time, Moses Alexander, even met with IWW members in the Abbott basement. As far as other purposes for the mysterious underground rooms, Renk says anyone's guess is as good as hers. "They certainly could have been used to hide booze during Prohibition or for some other illicit purpose," she said. "On the other hand, they could have a much more prosaic use." Based on the well-documented bootlegging and corruption happening in Sandpoint at the time- including the 1923 conviction of Bonner County Sheriff William Kirkpatrick for seizing and reselling more than 100 cases of bootleg whiskey- Evans said that "the basement rooms in the Walker and Abbott blocks were no doubt a location involved in the drinking of bootleg liquor." "You know that those rooms were involved in that," Evans told the Reader, "but it's hard to say why they built them in the first place." Why build hidden, underground rooms? Perhaps a more direct question: Why not? If anything, history buffs a century later itching for a glimpse of early Sandpoint will have a great time musing about the building's wild past. Plus, discoveries like this remind Upton why preserving Bonner County history is not only important, but also a lot of fun. "We can't renovate these rooms, but we can document them and make them a part of our history." By Hannah Combs

Jean Wright developed her passion for gardening from necessity, according to her daughter Bev Kee, first growing food during the Depression years, later adding perennials and flowering vegetation “to her repertoire.” By trading plants with friends, “she could make a beautiful garden out of next to nothing,” says Bev. The art of creating beauty from the earth has a long tradition in Bonner County. Some gardens serve a practical purpose, from the Depression’s kitchen gardens and the victory gardens of World War I to the back alley raspberry bushes and plum trees, overflowing with ripe fruit in the summer. These gardens were designed to feed us, but can’t help showering us with beauty too. And then there are the gardens that are designed to impress, like that of Cora Clagstone. Cora moved to north Idaho in the early 1900s with her husband Paul, and they established a sprawling cattle ranch near what is now Athol. A former Chicago socialite, Cora adapted quickly to the hard work of farming life, but she believed that women should take time for themselves to embrace the simple joys of their homes. In a public speech she encouraged all women to keep a garden, saying, “You will find the care of it the greatest pleasure, for not only will a few minutes a day do much for the flowers but for yourself as well.” Thanks to the profitable cattle business, Cora was one of a handful of “privileged pioneers,” according to her daughter’s memoirs. This meant she had almost unlimited resources to design the garden of her dreams. What started as a simple flower border along the house evolved into a full-fledged English garden, with a formal layout and cottage-style blooms. A horse team spent three days leveling the ground in preparation and laying down several tons of manure. At the center of the garden was a custom-built sundial, which Cora said “adds much to the picturesqueness besides keeping good time.” At one garden edge, she had a simple pergola of rough timbers “on which I have old-fashioned roses, clematis and bittersweet growing.” The enormous effort had been worthwhile: “The pleasure of caring for this garden, and, when busy sewing, looking out over its mass of blooms, is enormous.” The pleasures of gardening have bloomed for generation after generation in Bonner County. That’s what happened for Bev Kee and her siblings, learning to love the soil from their green-thumbed mother. Bev, now a gardener herself for many years, sees the practice as a form of art. She says, “It is fascinating to visit friend's gardens, or public gardens, and study the style and uniqueness of each garden. No two gardens are alike; they are the artistic personality of the creator.” With the landscape as the canvas and plants as the medium, every choice of color or curve of a pathway “adds style or character to each owner’s garden.” Bev believes the joy of gardening lies in sharing plants and starts with neighbors and friends. Not only does it bring people together, but it gives the plants stories that they carry from garden to garden. She says, “I particularly love the ability to design a new garden for someone using transplants from my gardens. There are many a garden in Sandpoint that have been created by someone pulling up their van or pick-up and hauling away enough transplants to start their entire garden.” Maybe you are a garden artist, adding dabs of color to your masterpiece every spring. Maybe you can’t wait to divide starts among your friends and neighbors in a few weeks. Maybe you’re hoping you can keep just one plant alive with your less-than-green thumb. Whatever the case, take pleasure in your garden. As Bev says, “Plant it, move it, share it, remove some, change design, repeat. Unlike a good book, it never ends.” By Helen Method Newton

Self-quarantining is not entirely new to Bonner County old timers. Seventy years and more ago, it was pretty much a way of life. Farm families especially were used to being home almost all of the time except for a few hours a day for the children who were at school. When cows have to be milked at 5 a.m. and 5 p.m., there isn’t a lot of time left to socialize. At the time we didn’t’ even know we were practicing social distancing. In late 1946, my father bought a 240 acre farm at the top of the hill just south of Northside School from the Berg brothers, two old Norwegian bachelors. The land was separated down the middle by the dirt county road, then known as the Farm-to-Market Road but now called Colburn Culver. We moved there in February 1947. My parents, Harold and Ruth (Fetty) Method, were of strong mid-western stock and they were not strangers to living without electricity and indoor plumbing. It was their first order of business to have both brought into the house. When what you eat is dependent upon what you raised or grew, attention had to be paid to keeping the cows healthy, raising chickens, occasionally a hog, and maintaining a very large garden and a few apple trees. Mother spent her summers planting, weeding and then harvesting and “putting up” (canning – freezers came years later) vegetables and fruit. It seemed that all summer long she kept the wood stove stoked and was either canning something or cooking for harvest crews. My father was busy from before dawn to after dusk tending to his 42 Holstein milk cows and plowing, seeding, and harvesting crops of hay and grain, all the while continually clearing more land of trees and stumps. September 1947 found me walking one mile each way to and from the Pack River School. It sat exactly where Northside sits today. We had one room, one teacher for eight grades, a large wood stove, and an outhouse and “the big kids” hauled water in from the well in the school yard. There was a small stable for the kids who were lucky enough to have a horse to ride to school. I envied them. I always wanted a horse but Daddy said, “A horse eats as much as two cows and the horse doesn’t produce any milk,” and selling milk was our only source of income. Whenever I share these early school day details, people look at me and ask incredulously, “HOW OLD are you?” Old enough. Limited socializing took place with an occasional visit to a neighbor’s home where coffee was shared and always served with a dish of canned fruit and/or something the hostess had just baked. These visits were spontaneous. No calling ahead. No phones. Our first phone had 12 homes on the party line. It provided another way to know what was going on in the neighborhood while practicing social distancing. By Hannah Combs

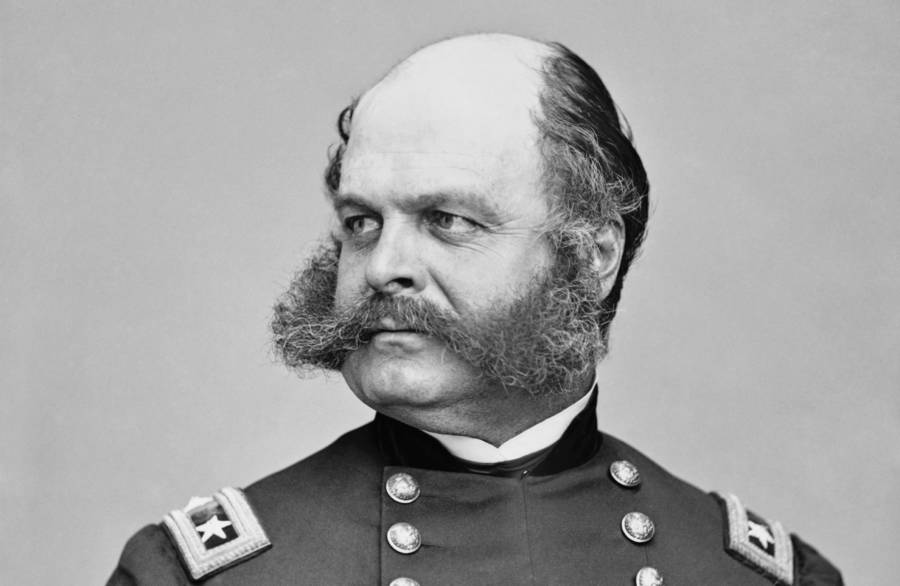

My first spring in Sandpoint, I visited a friend at her cabin, and she wouldn’t let me leave without a visit to “the big tree.” The property behind her home turned into a mass of creek channels during spring run-off, and she lent me thigh-high muck boots to slog through the frigid water. Clinging to shrubs, I propelled my way across, only looking up when I was on dry land again. I was standing in the shadow of the most incredible tree I had ever seen, a lone western red cedar whose fellows had been cut or fallen decades before. Over eight feet in diameter, it was stretching out into the creek, looking as though it might go for a walk at any minute. The interplay with water through the years had sculpted its lower trunk into a fantastical twisting growth of burl and roots. Coming from the Midwest, this first encounter with a “big tree” was a moving experience, waves of pure wonder pouring over me. For those who have lived their entire lives here, the imposing trees of the West may not be such a surprise, but they still inspire awe and respect. As one of our native species, cedars have played a role in Bonner County history for thousands of years. The cedar has been used by the Kalispel tribe for many daily practices, from building canoes and bark baskets to smoking fish, and cedar is still a popular building material, cut and milled for everything from roofing shingles to guitar soundboards. Cedar forest provides wildlife habitat for species like black bears and hairy woodpeckers, and old growth stands are resilient to forest fires, because they do not support the dense understory that provides fuel for the fire. After more than a century of human development, pockets of old growth cedar can still be found close to home. Though the Roosevelt Grove of Ancient Cedars northwest of Priest Lake and the Ross Creek Cedar Grove just across the border in Montana are two of the most popular places to stand among these giants, cedars can be found all over Bonner County. The “Grandfather Tree” at Schweitzer is one iconic example. Nestled near the Springboard run in the Outback Bowl, the towering cedar can be discovered in the winter or summer months, though a summer hike might entail more of an expedition. Though neither native to North Idaho nor as imposing as the cedars, the magnolia tree’s history goes much further. Known for its exquisite and ephemeral pale blooms, the magnolia was one of the earliest flowering plants, developing during the Cretaceous Period. The fossil record shows magnolias on Earth as early as 95 million years ago. The magnolia developed some interesting characteristics throughout its ancient past. "The petals of the magnolia flower are quite strong and feel thick to the touch compared to other petals," says local gardener and BCHS Volunteer Coordinator Jacquie Albright. The magnolia was around before bees and butterflies, so it adapted for a different pollinator. "The petals have to be strong enough to hold a beetle as it enters into the centre of the flower." Though the oldest magnolias are native to eastern Asia and eastern North America, its 200+ subspecies have adapted to a variety of climates, including North Idaho's. With blooms that usually appear before the leaves, magnolias always put on a stunning early spring display, which can be seen throughout our community. The magnolia is the state flower of Mississippi, where the record-holding largest tree stretches to 122 feet and has a diameter of over 6 feet. Bonner County is home to a few record trees of its own. The University of Idaho Big Tree Program recognizes six Bonner County trees as the largest in the state: the Douglas maple, red alder, butternut, subalpine larch, paper birch, and black cottonwood. The record-holding subalpine larch can be found near the upper Roman Nose lake. The paper birch and black cottonwood can both be seen on the Gooby farm near the base of Gooby Rd. The Sandpoint Tree Committee’s Outstanding Trees of Sandpoint, Idaho booklet says of this black cottonwood, “This multistem giant measures 8 feet in diameter and reaches a height of 113 feet.” The black cottonwood’s sap was used by some Native American tribes as a glue or even for waterproofing, and today its flower buds are used in some perfume fragrances. Whether your favorite tree is hidden deep in an old growth forest or on colorful display for everyone to see, take a moment this spring to visit your tree and stand in awe of its beauty. The history of these ancient species precedes us, and there is much to learn from their grace and resilience. Research courtesy of U.S. Forest Service, Sandpoint Tree Committee, University of Idaho, Jacqueline Albright.  General Ambrose Burnsides was as famous for his sideburns as he was for his military accomplishments in the Civil War. General Ambrose Burnsides was as famous for his sideburns as he was for his military accomplishments in the Civil War. By Hannah Combs Have you found yourself lately standing in front of the mirror, hoping that quarantine will last the three months it takes to flesh out a proper handlebar mustache? Have you gone crazy wrangling squirmy children while giving them lopsided haircuts? Have you taken the midnight plunge into the irretrievable world of bangs? We’ve been seeing a lot of creative home haircuts in the past weeks. In an effort to distract you from the agonizing mustache wait or your fidgety children, and to give you one last chance to rethink the bang situation, we’re sharing the surprising history behind some of the most iconic hairstyles of the past. The beehive was one of the most dramatic and accessible looks of the 1960s and is still favored as a showstopper by the likes of Beyoncé. In 1960, Modern Beauty Shop magazine commissioned Chicago celebrity hairstylist Margaret Vinci Heldt to bring life back to the stale world of hair. Heldt designed the style to fit under a particular fez hat she adored. When the towering look was assembled for the magazine, Margaret took the hatpin from her fez, shaped like a bee, and adorned the hairdo with it. With that, the beehive was born. Expected to be a passing fad, Heldt was shocked by the longevity of the hairstyle’s appeal. But for millions of women around the world, she had hit upon an idea that made a statement and was actually quite easy. The beehive relies upon two simple techniques: backcombing and lots of hairspray. For women who had spent hours curling their hair for the intricate hairdos of the previous decades, it was a no brainer. Hairspray had become ubiquitous after it was ingeniously paired with the aerosol can in 1948, and backcombing, though destructive on split ends, was a fast way to achieve volume. Another look known for dramatic volume was that popularized by Ambrose Burnside, a Union general who led several battles of the Civil War as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Thanks to developments in the art of photography, his other legacy is not soon to be forgotten: that of the epic sideburns. Though not the first to sport the distinguished look, Burnsides was incredibly proud of his facial hair, and as a prominent figure in society, the look was named after him. Legend says that as a young cadet at West Point (and a bit of a trickster), Burnsides first donned the distinctive look to skirt a rule against long beards. By shaving his chin, he was able to sidestep the rules, and he never looked back. As many of us have discovered, there’s another common hairstyle you can’t easily go back on: the bangs. Love them or hate them, they have ridden the waves of hair history for more than a millenium. Though often thought to have originated with Ancient Egyptians, thanks to depictions of Cleopatra in film, surviving Egyptian wigs merely show longer strands or braids of hair placed low across the forehead. True bangs, cut in a fringe, were first popularized by a Persian musician and polymath known as Ziryab. He was invited as a cultural diplomat to the Cordoba court of early Spain in 822 and started one of the first music schools that was open to both male and female students. He took his role seriously, and aside from influencing popular hairstyles and fashions, he also promoted hygiene practices like dental care, regular bathing, and treating hair with fragrant oils. Bangs reappear in many forms throughout history, and by the 1920’s they were cemented in our hairstyle vocabulary by fashionable flappers like Louise Brooks. Whether you want to extravagantly style your facial hair, dye your hair with food coloring, or bravely take the scissors to your locks, there’s no time like the present to experiment. History provides thousands of do’s and dont’s for your entertainment and inspiration. Or maybe it seems wiser to wait until the salon opens and hand your hair over to the professionals. However it turns out, don’t split too many hairs over it, just have fun! Research courtesy of Helin Jung, Silk Road Rising, and the American Battlefield Trust. By Hannah Combs The Bonner County Historical Society has created a portal where you can share your stories, photos, and artifacts about the COVID-19 experience. Your personal histories will be archived in the Museum’s collections so that years from now you can remember what it was like, and so that future generations can understand what we are all going through. BCHS has been collecting personal histories since its inception in the early 1970’s. Most of these can be found recorded in the oral histories collection. These are two stories about the Spanish influenza that were recorded as part of longer life histories. Vernice Stradley, interviewed by Ann Cordes in 1978, was in high school during the winter of 1918-1919. She said they closed her school before the year ended, and she was home with her family for the remainder of the year. A hundred years ago, there was no way to go to school remotely. Several of her family members got the flu, and though she and her brother recovered quickly, her mother had to be transported to a larger hospital for treatment for a lung infection complication. Vernice said, “They took her away sick. They had a Dinky [a short shuttle train] that went through here, and they stopped the Dinky right by the house.” During her mother’s three-month hospitalization, the family received infrequent updates on her condition and were not allowed to visit. “They didn’t think she was going to live for awhile. [...] they said it was only a matter of time,” recalled Vernice. But her mother overcame the flu, went on to have one more child, and Vernice went back to school the following year and completed her high school degree. Vernice said she “never gave up. I bet I got as good an education then in high school as they get now when they get out of college.” Frances Wendle Miller’s family was in the process of moving from Chicago to Hope at the beginning of the flu epidemic. Her father had moved first to establish a home and business (he was a doctor for a lumber mill in Hope), and Frances recalled, “We’d come to visit and we’d have to wear masks on the train.” They had a set of clothes they would wear on the train, then immediately change when they reached the house and wash all of the train clothes, for fear of infection. Shortly after the family settled in Hope, they relocated to Sandpoint, because her father’s medical skills were needed to help treat flu patients at the Page hospital. Frances said, “We could climb the tree [in front of the hospital] and watch them operate in the operating room.” She acknowledged that the flu hit the area hard and that “it made us more careful.” Frances Wendle Miller was interviewed by Nancy Nelson in 1978. In addition to sharing current COVID-19 experiences, please let us know if you have family stories about the Spanish flu in Bonner County. What was the experience like for your parents or grandparents? Have you ever visited the “Little Lambs” section of Lakeview Cemetery, dedicated to the children who died during the Spanish flu? If you have something to share, please feel free to include it in your portal submission and help enrich the Museum’s collection.

Research courtesy of the Bonner County History Museum. By Hannah Combs Since the last of the snow melted, I have been scattering small piles of birdseed around the lawn, trying to lure songbirds to a newly established birdfeeder. Every now and then, a quartet of mule deer stroll through and nibble bits of corn from the piles of seed. So sweet and fuzzy, I thought. I felt like Snow White, friends with all the forest creatures. Then I planted a beautiful tulip, its blossoms a delicate purple that stood out as a beacon of spring. The next morning, it was chomped to the ground, bulbs scattered haphazardly, a tender treat for the mangy, dastardly creatures that dared to step foot in my garden. Sound the alarm, I cried. Dispatch the sentries! The villains will surely be back to wreak havoc again! Throughout our history, we have had a tendency to dramatize animals, whether by reading into the fiendish motivations of hungry deer or by putting costumes on our dogs. If you think that our obsession with humanizing and befriending animals is a new phenomenon born of technology-aided boredom, think again. In the early days of Bonner County, our ancestors maintained quite the menagerie of wild animals. Frank Clements was known far and wide for his two pet deer, Babe and Buster. They were a regular sight around Sandpoint, pulling a custom-made buggy. Clements entered the dynamic pair into exhibitions around the northwest, and as BCHS historian Dan Evans says, “Boy, could this guy tell stories.” Buster and Babe allegedly could read, walk a tightrope, and enjoyed listening to ragtime music. Clements once told a newspaper that he refused an offer from a circus manager of $50,000 for Babe and Buster, “the equivalent of $1.3 million today,” said Evans. In 1915, Clements set out with Buster and Babe on a world-record expedition from San Francisco to New York. It appears that they made it at least as far as Chicago, where Frank eventually settled and began training reindeer. Equal to Clements as a master of drama, both in her cinema and real life, Nell Shipman kept several pet bears at Lionhead Lodge at the north end of Priest Lake, which she used in some of her film projects. The most famous bear-keeper of all, however, was Ms. Mary Matilda (Timblin) Hunt, who owned the Great Northern Hotel in Sandpoint. One August day in 1910, when a Sandpoint Interurban Railway street car was stopped and unattended on the tracks, one of Ms. Hunt’s pet bears broke out of its enclosure, climbed aboard the street car, and ate over six pounds of butter that were destined for local deliveries. When motorman Dick Turpin returned from an errand, he “was thunderstruck at the audacity of the bruin, but lost no time in hastening to the car and assisting the bear out one of the side doors,” according to the local paper. Wild animal adventures may have become smaller-scale over the years, but they still abounded. In 1984, as a prank retirement gift, Idaho Fish and Game transplanted 28 eastern fox squirrels from Boise to former IFG commissioner Pete Thompson’s home in the Selle Valley. Seven years later, the non-native species had spread far and wide, thanks to few natural predators. Though Thompson defended the squirrels, saying “I can’t see they do any damage,” opinions differed, particularly among people whose gardens were munched on by the rodents. Today, the “town squirrels” have traveled at least as far as Sagle, though no one knows how they hitched a ride across the Long Bridge. As entertaining as these stories may be, it is our responsibility to enjoy them as relics of the past and not add to the canon of questionable wildlife interactions. In recent years we have established healthier boundaries with wild animals, thanks to ever-evolving research about animals’ natural habits and habitats. We know how quickly non-native species introduction can disrupt an ecosystem. We’ve learned that we shouldn’t harness deer to our golf carts and fat bikes. As black bears come out of hibernation, we’ll keep our garbage cans inside, so they forage for carrion instead of carry-out. We’ll remember that the neighborhood moose is a powerful and unpredictable creature, and for that matter, so are a lot of our dogs, even the ones wearing costumes. And I’ll stop channeling Snow White, in the hopes that the muleys will head back to high ground for the summer, instead of plaguing me with their tulip-devouring mischief, or as they might say, natural habits. Research courtesy of the Bonner County History Museum, local historian Dan Evans, Bev Kee, the Seattle Times, and Idaho Fish & Game. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed